Four years ago today, I published the first post on this blog. As I hit the publish button, I knew that doing so could dramatically impact my life and the lives of many others. It was a decision I had been stewing over for a year at that point, but by the time we launched this blog, there was too much at stake to stop. Just the day before, my wife, my daughter, and I had moved out of the Philadelphia area. Our new house was filled with unpacked boxes, and I had just returned the U-Haul truck earlier that morning. Three days later, three people who had been born into MOVE planned to go public on this blog and the Murder at Ryan’s Run podcast. One of them was going into hiding with her children, fearing for her life.

All of us had serious concerns for our safety as we came forward with the truth about MOVE. These former members had been threatened for their entire lives that if they ever publicly talked about the things they came forward with, they would be killed. On September 26th, 2002, John Gilbride was murdered, and violence had been used to control members throughout MOVE's history, so these fears were not unfounded. In the following weeks, many, many more former MOVE members and supporters came forward with serious allegations against the cult.

Recently, the Murder at Ryan’s Run podcast began releasing regular episodes again. That, and this fourth blog anniversary, has caused me to reflect on what has transpired since we launched the blog. It’s a bit strange, as I haven’t regularly posted on this blog in three years. However, one of my missions in starting this blog was doing a small part to add a few breadcrumbs to the path to help others out of cults. When I was trying to find my way out of MOVE, I benefited greatly from the posts on antimove.blogspot.com, as well as many other firsthand accounts from people who had left cults. My experience of going public with my knowledge of MOVE and then moving on with my life would have been helpful for me to read five years ago.

For over twenty years, MOVE consumed a significant percentage of my thoughts. For much of the first decade, they were the thoughts of an obsessed devotee. For more than the last decade, I was trying to figure out how to get out of MOVE without blowing up every other aspect of the life I’d created within its web. Even when I thought I’d freed myself from MOVE’s thought-stopping indoctrination, a great deal of my time was still spent trying to navigate the fact that my daily schedule was still significantly impacted by MOVE.

Once my wife, Maiga, and I were on the same page and had decided we needed to come forward to push for justice for John Gilbride and to support the former MOVE members who were ready to come forward, my life became even more dominated by MOVE, for a relatively short time. The six months that followed were intense, and much of our time was consumed by writing blog pieces, conducting occasional interviews, and responding to questions via email. It felt as though we needed to do all we could to draw attention to the situation in the hope of keeping the former members who had left out of danger, and trying to highlight John Gilbride’s murder while there were some people paying attention.

What I didn’t expect, and what I think may be helpful for anyone who is reading this while stuck in a cult to hear, is the huge degree to which I rarely ever think about MOVE now. My world has become so much bigger and more beautiful since moving on from MOVE. I could not have imagined how much better it could get. MOVE is no longer my reference point for things, either positively or negatively. If I consciously start thinking about Bert and Ria, the abuse the kids in MOVE have suffered, all of the money that they’ve stolen and conned from people over these last 50 years, or the murder of John Gilbride, then, obviously, I feel as angry as I ever have. I still desire the crimes of those in MOVE’s leadership to be publicly recognized and prosecuted. However, they are no longer significantly impacting my day-to-day life. And as I look back at them now, specifically Ria and Bert, I don’t see powerful people, I see pathetic, yet still incredibly dangerous, shells of people who sold their souls for cheap, sadistic power and a nonsensical ideology.

Looking back four years later, I can see that there was nothing of substance within MOVE from the start. Vincent Leaphart/John Africa wove together strands from many other religions, philosophies, revolutionary and New Age movements, tied them together with his own charisma and persuasiveness, and trained dozens of people thirty years his junior to psychopathically defend him to their deaths or the deaths of their children. When you start to pick away the layers of MOVE, there’s nothing there except for Leaphart’s pathologies and a bunch of odds and ends he cobbled together from others. The belief system eventually just becomes a vehicle for whoever is in power in the cult to exploit and abuse those under them, while profiting mightily. MOVE latches onto some noble causes and some legitimate critiques, but only as a vehicle for their own self-absorbed agenda. Five years ago, when I first started talking to Beth McNamara of the Murder at Ryan’s Run podcast, I thought that there was some substance at the center of MOVE. Her work and my conversations with the MOVE survivors convinced me that MOVE’s only belief is in its own self-serving ends.

When we launched the blog and former MOVE members began coming forward, we hoped that Ria, Bert, and others would be held criminally responsible for the murder of John Gilbride, the abuse inflicted on children in MOVE, and much more. Though that didn’t happen, I still feel like we won. The entire MOVE Organization has splintered, and, other than the con still being run by Mike Africa Jr., is almost non-existent. None of the original MOVE members seems to be doing public events, older members have split into many factions who don’t speak to one another, and almost none of the second and third generation members still call themselves members, while many have publicly condemned the group.

Deciding to leave a cult can feel impossibly difficult. One has to contend with the fact that they have wasted many of their best years, sacrificing themselves for something destructive and empty. Even once one navigates that psychological hell, they still have to find a way to physically extricate themselves, which can be dangerous or financially untenable. But even once that challenge has been conquered, there is still at least one last temptation to face: becoming obsessed with fighting against the cult. This is an easy trap to fall into because fighting against the cult can become your new center of orientation, and trying to destroy the group can fill the void of meaning that work within the cult once filled. Many more years can easily be lost in this way.

I am very happy that I decided to come forward and write about the things that I knew. I don’t think that I ever would have been able to fully move on and leave all of this behind had I not done so. I would have also continued to feel guilt about not speaking up for justice for John Gilbride. To anyone who is in the situation I was in within another cult, I strongly recommend speaking out, so long as you take all of the possible safety precautions. However, beware of the trap of making the fight against the cult your new identity.

I will continue to reflect on my experiences in MOVE for the rest of my life. I will likely feel inspired to write on this blog again on an anniversary or if there is a related event in the news. If John Gilbride’s murderer is ever brought to trial, that would reignite a passion in me to push for justice. However, now, in my day-to-day life, MOVE is no longer present. I honestly did not ever expect that to be the case. Four years later, I could not be happier to have left MOVE.

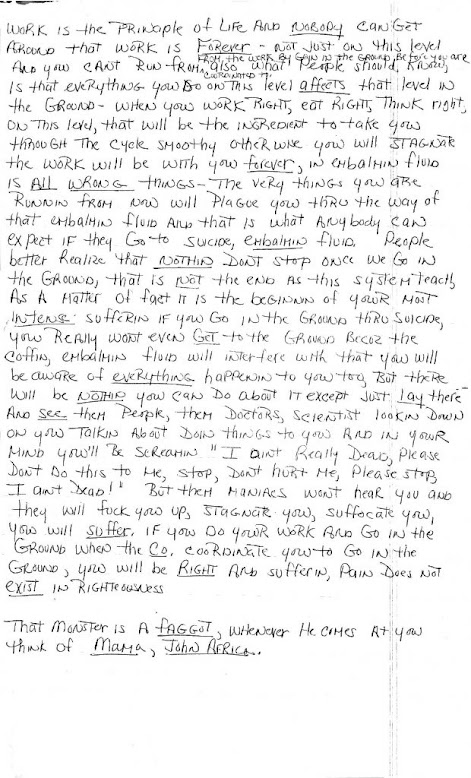

Sunset over Philadelphia, taken from across the Delaware